About the author: Raised in Mumbai and currently living in Bangalore, Neel Saraf is a 12th Grade student at The International School Bangalore. Alongside his interests in finance and football, Neel is passionate about making a lasting impact in his community. His academic pursuits include Economics and clean energy. He aims in the future to contribute to sustainable progress.

Abstract

India, a country acclaimed as the fastest-growing major economy, stands at a pivotal juncture where economic expansion converges with environmental responsibility. In this context, addressing the poor financial health of electricity distribution companies (DISCOMs) is crucial for ensuring the success of India’s clean energy transition. This paper seeks to analyze the challenges posed by the financial distress of DISCOMs and its impact on renewable energy adoption in India. By drawing lessons from Vietnam’s energy policy reforms, this research aims to provide actionable insights for enhancing the financial health of DISCOMs, thereby supporting India’s sustainable energy goals.

Introduction

India’s commitment to addressing climate change and transitioning to cleaner energy sources is underscored by its ratification of the Paris Agreement in April 2016. Before this, India submitted its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) in 2015, which have been surpassed ahead of schedule (Press Trust of India, 2023). As such, at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow in 2021, Prime Minister Modi announced the Panchamrit or the five-point agenda to combat climate change:

- Reaching 500 GW non-fossil energy capacity by 2030 which is currently at 203 GW according to the Central Electrical Authority (2024)

- Fulfilling 50% of India’s energy requirements through renewable energy by 2030

- Reducing total projected carbon emissions by one billion tons from now to 2030

- Reducing the carbon intensity of the economy by 45% by 2030 over 2005 levels (33% as of 2019)

- Achieving the target of net zero emissions by 2070

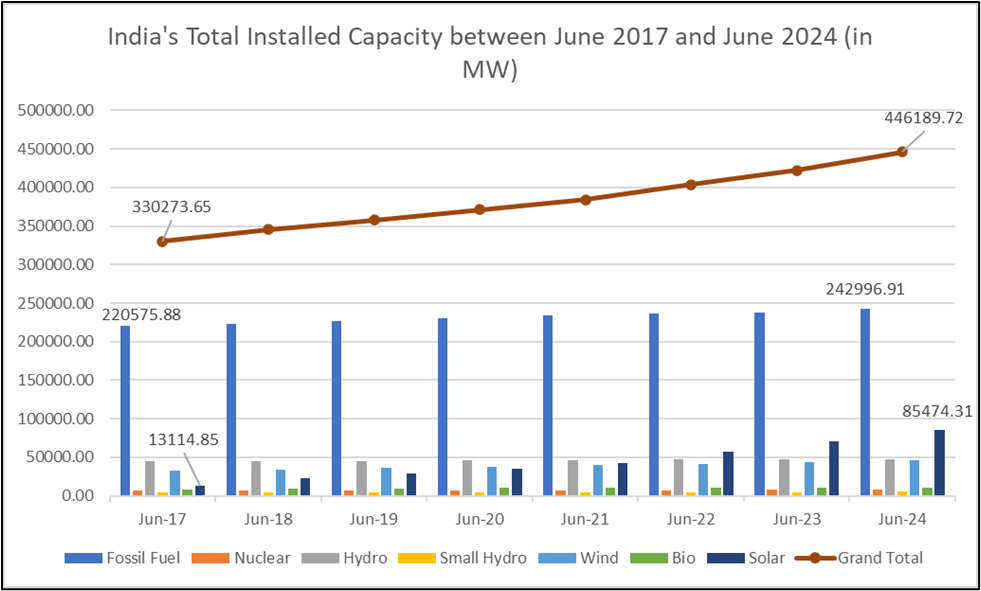

Source: Central Electrical Authority’s Installed Capacity Report from June 2017 to June 2024 (Central Electrical Authority, 2024)

The above figure illustrates India’s evolving energy landscape between June 2017 and June 2024, showing the total installed capacity of different energy sources. Over these seven years, there has been significant growth in the country’s total installed capacity, which increased from 330,273.65 MW in June 2017 to 446,189.72 MW (~35%) in June 2024. This growth trajectory highlights India’s efforts to expand its energy infrastructure to meet rising demand, as the country seeks to balance energy security with sustainable development.

Fossil fuels have remained the largest contributor to India’s energy capacity, increasing by ~10% in this period. Nevertheless, there has been considerable renewable energy capacity addition, increasing by ~85% in this period. Among renewable energy sources, solar energy stands out for its growth: an impressive 550% increase in capacity during this period This sharp rise demonstrates India’s commitment to renewable energy, driven by favorable government policies such as the PM KUSUM solar pump policy, falling costs of solar technology, and the growing recognition of the need for sustainable energy solutions.

Clean Energy Transition Challenge: Poor Financial Health of DISCOMs

Electricity distribution companies, commonly known as DISCOMs, play a crucial role in the power sector by managing the distribution and retail supply of electricity to end consumers. They serve as the final link between power generation and consumption, ensuring that electricity generated by power producers reaches residential, commercial, and industrial users. In India’s energy landscape, DISCOMs are responsible for maintaining grid stability and are key actors in the nation’s clean energy transition. Their performance directly affects not only the electricity sector but also the broader economy, influencing energy access and affordability.

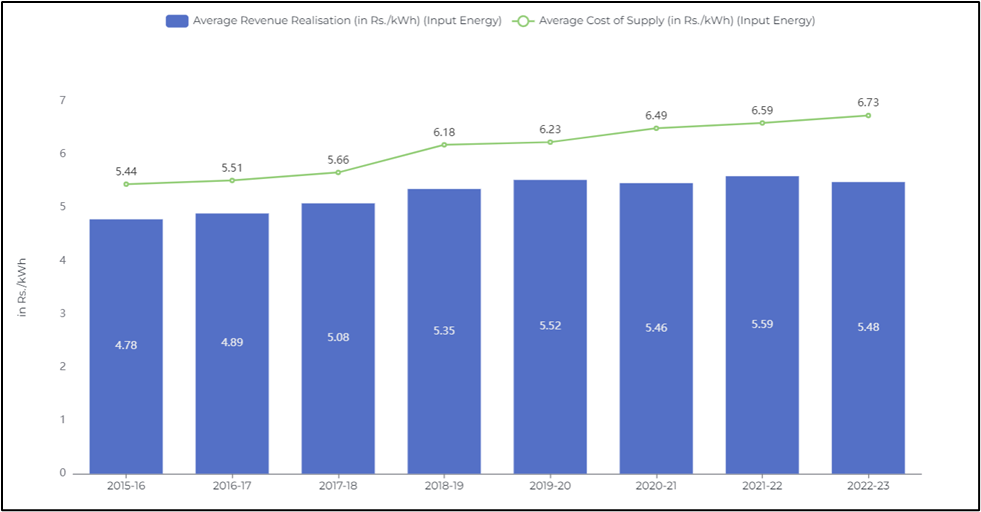

To foster renewable energy adoption, India has implemented the Renewable Purchase Obligation (RPO) policy. This policy mandates that DISCOMs, open-access consumers, and captive power producers procure a specific percentage of their electricity from renewable energy sources (Poswal, 2024). The RPO target has been consistently raised over the years to align with India’s clean energy ambitions. For the year 2023-24, the Ministry of Power set an RPO target of 24.61%, highlighting the government’s commitment to accelerating renewable energy adoption (Rishi, 2022). Nevertheless, many DISCOMs have struggled to meet their RPO targets due to their poor financial health. This financial distress stems from high levels of debt, unpaid subsidies, and inefficiencies in revenue collection. Figure 2 below illustrates a key challenge facing DISCOMs, showcasing the gap between the average revenue realization, which is the revenue that DISCOMs receive per unit of electricity sold, and the average cost of electricity supply, which represents the total cost incurred in supplying electricity, including procurement, transmission, and distribution expenses.

Source: NITI Aayog’s India Climate and Energy Dashboard (2022)

From 2015-16 to 2022-23, there has consistently been a gap between the cost of supply and the revenue realization. While the average cost of supply has risen steadily, reaching Rs. 6.73 per kWh in 2022-23, the average revenue realization has failed to keep pace, remaining at Rs. 5.48 per kWh in the same year. This persistent revenue-cost gap indicates that DISCOMs are unable to recover their expenses, which results in mounting financial losses.

These financial constraints severely limit their ability to invest in the infrastructure upgrades required to integrate renewable energy into the grid and also fulfill their RPO mandates. Only 5 states in India have been compliant with their RPO targets, with the others falling behind), which also damages investor confidence and hinders RE expansion (Poswal, 2024).

Consequently, despite regulatory mandates like the RPO, the poor financial health of DISCOMs remains a major bottleneck in India’s transition towards renewable energy.

India’s Response: Revamped Distribution Sector Scheme (“RDSS”)

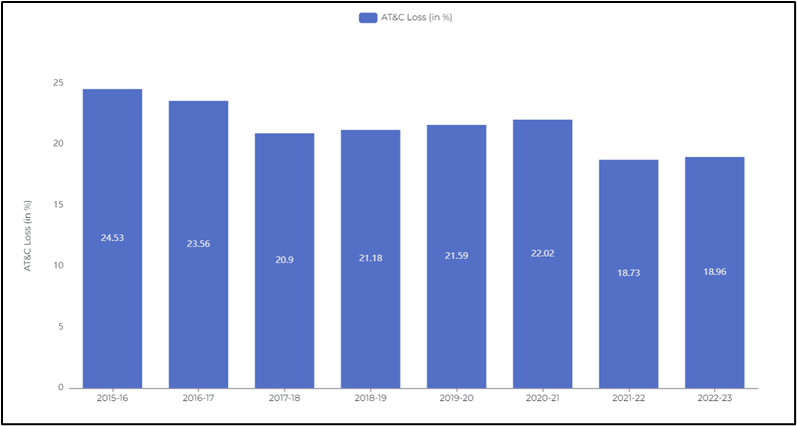

The Government of India launched the Revamped Distribution Sector Scheme (RDSS) in 2021 as a comprehensive initiative to address the persistent challenges faced by electricity distribution companies (DISCOMs). This scheme represents a significant effort to reform the power distribution sector, which has long been considered the weakest link in India’s electricity value chain (Press Information Bureau, 2023). Key tangible targets of the RDSS include reducing Aggregate Technical & Commercial (AT&C) losses to 12-15% across India. AT&C losses represent the total technical and commercial losses in the distribution network, including energy lost during transmission and distribution, as well as revenue losses due to inefficiencies such as theft, non-payment, and billing errors. As per Figure 3, in 2022-23, India’s AT&C losses were ~19% which is significantly higher than the global average of 8.1% (Gussan et al, 2016).

Source: NITI Aayog’s India Climate and Energy Dashboard (2022)

Additionally, RDSS also aims to eliminate the gap between the Average Cost of Supply (ACS) and Average Revenue Realized (ARR) by 2024-25. The scheme is structured into two main parts: Part A focuses on financial support for prepaid smart metering, system metering, and distribution infrastructure upgradation. Part B emphasizes training, capacity building, and other enabling activities. Training and capacity building equip DISCOM staff with the skills needed to manage new technologies and efficiently implement reforms, which is critical for the success of infrastructure upgrades. Additionally, enabling activities, such as stakeholder engagement, help in creating awareness and cooperation among local communities and customers, facilitating smoother implementation of reforms (Indian Ministry of Power, 2021).

One of the strengths of the RDSS is its comprehensive approach, which addresses the technical and managerial aspects of DISCOM operations. The scheme’s emphasis on smart metering and IT enablement can potentially transform billing efficiency and reduce losses. Additionally, the RDSS introduces a results-linked financing mechanism, where the release of funds is contingent upon DISCOMs meeting pre-qualifying criteria and achieving basic minimum benchmarks. These benchmarks include reducing AT&C losses, improving billing efficiency, and enhancing collection rates. The mechanism ensures that financial support is tied to tangible improvements in DISCOM performance, thereby incentivizing efficient operations and fostering accountability. By making funding conditional on performance, this approach encourages DISCOMs to prioritize reforms and adopt best practices, ultimately contributing to improved financial health and service quality. This approach incentivizes performance and encourages DISCOMs to implement reforms more effectively (Indian Ministry of Power, 2021).

The Average Cost of Supply (ACS) and Average Revenue Realization (ARR) have further diverged in 2022-23. The gap between ACS and ARR continues to widen, highlighting the ongoing financial strain faced by DISCOMs. The divergence can be attributed primarily to poor tariff rationalization, which has led to DISCOMs being unable to recover their costs adequately.

Tariffs, in the context of electricity, refer to the pricing structure that determines how much consumers pay for the electricity they use. Generally, they should cover the costs of generating, transmitting, and distributing electricity, as well as administrative expenses and margins for distribution companies Tariff rationalization is the process of aligning electricity tariffs with the actual cost of supply, ensuring that DISCOMs can recover their expenses and maintain financial sustainability. However, in India, the current tariff system has significant shortcomings, which the RDSS has failed to address.

India’s electricity tariffs are regulated by State Electricity Regulatory Commissions (SERCs) under the broad guidance of the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC). The Indian tariff structure is characterized by cross-subsidization, where industrial and commercial consumers pay higher tariffs to subsidize the lower rates for agricultural and residential users. This system is intended to make electricity affordable for vulnerable sections of society, but it also burdens industrial and commercial users disproportionately. For example, commercial users are charged tariffs 55% higher than the national average power supply cost, while industrial users face tariffs 25% higher (Einrac, 2023). Conversely, domestic and agricultural consumers benefit from tariffs that are 30% and 90% lower than the cost of power supply, respectively. While this approach is politically popular, it significantly strains the financial viability of DISCOMs (Einrac, 2023).

Power Purchase Cost (PPC) is the largest expense for DISCOMs, accounting for 65-75% of their total costs. PPC is heavily influenced by the price of coal and the cost of newer renewable energy technologies. In addition to PPC, transmission charges and operations and maintenance (O&M) expenses also contribute substantially to the overall cost structure. Despite these high costs, DISCOMs are often unable to adjust tariffs annually to reflect changes in generation costs, primarily due to regulatory and political interference (Einrac, 2023). Tariff adjustments are frequently delayed to appease voters, resulting in tariffs that are set below the actual cost of supply. This practice leads to revenue shortfalls, accumulating debt, and ultimately a growing gap between ACS and ARR.

The expansion of energy access through initiatives like Saubhagya has been successful in connecting more households to the grid, but it has also increased the number of low-paying consumers. Government subsidies for agriculture and other sectors further exacerbate the financial strain on DISCOMs, contributing to a rise in retail tariffs for non-subsidized consumers. The combination of high transmission losses, delayed tariff adjustments, and the burden of cross-subsidization has left DISCOMs financially vulnerable and unable to invest in necessary infrastructure upgrades.

Energy Sector Tariff Reforms in Vietnam

Vietnam’s experience in reforming its power sector offers valuable lessons for India, particularly in addressing the weaknesses of the RDSS. Both countries have experienced rapid economic growth and increasing electricity demand. Vietnam’s GDP growth averaged 6.23% annually from 2000 to 2024, (Trading Economics 2023) while India’s averaged 7.01% in the same period. This economic growth has driven a surge in electricity consumption, with Vietnam’s increasing nearly 9-fold from 22.4 TWh in 2000 to 192.9 TWh in 2018 (lượng, 2019), and India’s more than tripling from 384 TWh to 1,329 TWh over the same period (Jaganmohan, 2021).

Moreover, both nations faced similar challenges in their power sectors, including high technical and commercial losses, inadequate infrastructure, and reliance on government subsidies. However, Vietnam has made remarkable progress in improving its power sector’s efficiency and financial health. Electricity of Vietnam (“EVN”)is the state-owned corporation responsible for electricity generation, transmission, and distribution across Vietnam (Do & Sharma, 2011). In 2022, EVN’s total revenue from electricity sales was 494,359.28 billion VND, with an average selling price of 1,953.57 VND/kWh. The total cost of electricity production amounted to 441,356.37 billion VND, with a corresponding cost of 1,744.12 VND/kWh (Vietnam Energy Online, 2024). Additionally, Vietnam reduced its Transmission and Distribution (T&D) losses from over 20% in the early 2000s to around 9% by 2014 and also achieved universal electrification by 2017 (Trading Economics, 2020).

Before the reforms, Vietnam’s electricity tariff structure was heavily regulated, with tariffs set below the cost of supply to ensure affordability for consumers. However, this led to significant financial strain on EVN, which struggled to cover its operational and investment costs. The low tariffs also discouraged private investment in the power sector, as returns were insufficient to justify the risks involved. This situation mirrors the situation India’s power sector and DISCOMs face currently (World Bank, 2020).

The goals of the tariff reform were to establish a sustainable pricing mechanism that would ensure the financial viability of EVN while attracting private investment to meet the growing electricity demand. The government aimed to gradually increase tariffs to reflect the actual cost of electricity generation, transmission, and distribution, thereby reducing subsidies and improving the financial health of the power sector (Asian Development Bank, 2015).

Policy Recommendations

Based on the four tariff reforms observed in Vietnam, India can derive several policy recommendations to improve the financial health of DISCOMs and ensure a successful clean energy transition. Firstly, India should develop a clear, phased roadmap for tariff adjustments over the next decade, similar to Vietnam’s approach. This roadmap should gradually increase tariffs to reflect the actual costs of electricity generation, transmission, and distribution, ensuring that DISCOMs can recover their operational expenses and achieve financial viability. The gradual nature of these increases will help minimize the impact on vulnerable populations while providing time for industries and consumers to adapt. Additionally, this approach also addresses the RDSS’s weakness in tackling political interference in tariff settings by creating a long-term, transparent plan that is less susceptible to short-term political pressures. A phased and transparent tariff reform plan can help reduce the influence of political considerations on tariff levels, ensuring that DISCOMs can achieve financial sustainability while maintaining affordability for vulnerable groups.

A key aspect of Vietnam’s reform was the annual review and adjustment of base tariffs to ensure cost recovery. India should adopt a similar mechanism where State Electricity Regulatory Commissions (SERCs) conduct yearly assessments of tariffs to ensure they remain aligned with changes in generation and distribution costs. This adjustment process should be transparent and less influenced by political considerations, which will enhance the financial sustainability of DISCOMs and foster investor confidence in the sector.

Furthermore, Time-of-Use (ToU) pricing, where electricity rates vary depending on the time of day, can help manage peak demand and improve grid efficiency. Maharashtra has already implemented ToU pricing successfully, with significant improvements in managing peak loads and promoting energy conservation. By expanding ToU pricing across India, DISCOMs can incentivize off-peak usage among industrial and commercial consumers, thereby reducing pressure on the grid during high-demand periods and encouraging more efficient use of energy resources (World Bank, 2020).

And finally, Vietnam’s experience shows that cross-subsidies between different customer classes should be gradually reduced to ensure that tariffs are aligned with the cost of supply. In India, this would involve eliminating cross-subsidies where industrial and commercial users bear the burden of subsidizing residential and agricultural consumers (World Bank, 2020). However, cross-subsidies should be retained for high-cost rural areas where distribution costs are significantly higher, thus protecting vulnerable populations while improving cost efficiency for DISCOMs. For example, Karnataka has taken steps to gradually increase tariffs for agricultural users while offering incentives for adopting efficient irrigation technologies such as solar pumps under the PM-KUSUM scheme. This approach helps to reduce the financial burden on DISCOMs while promoting energy conservation and efficiency among agricultural consumers.

Conclusion

This research has examined the impact of the poor financial health of electricity distribution companies (DISCOMs) on India’s clean energy transition and explored potential lessons from Vietnam’s energy sector reforms. The findings indicate that the persistent gap between the Average Cost of Supply (ACS) and Average Revenue Realization (ARR), combined with high Aggregate Technical & Commercial (AT&C) losses, presents a significant impediment to achieving India’s renewable energy targets.

The study has critically evaluated the Revamped Distribution Sector Scheme (RDSS), noting its limited effectiveness in addressing crucial issues such as tariff rationalization. The comparative analysis of Vietnam’s reform experience has yielded valuable insights, particularly regarding the implementation of gradual, market-oriented reforms in the electricity sector. By adopting these recommendations, India can move towards a more financially sustainable electricity distribution model. Phased tariff reforms, reducing cross-subsidies while protecting the vulnerable, implementing time-of-use pricing, and ensuring annual tariff reviews will collectively address many of the current challenges faced by DISCOMs. This comprehensive approach will not only stabilize the financial health of DISCOMs but also support India’s broader clean energy transition goals. Improving the financial viability of DISCOMs will enable increased investment in grid infrastructure, which is crucial for integrating renewable energy sources into the grid. Moreover, a financially healthy DISCOM sector will be better positioned to meet Renewable Purchase Obligations (RPOs), thereby increasing renewable energy uptake. Enhanced investor confidence resulting from transparent pricing and financial sustainability will also attract more private investments in renewable energy projects, accelerating India’s shift towards a greener energy mix.

References

- Arvind Poswal. How Renewable Purchase Obligation Targets Can Advance Energy Transition in India. Down to Earth, 13 May 2024, www.downtoearth.org.in/renewable-energy/how-renewable-purchase-obligation-targets-can-advance-energy-transition-in-india-96101.

- Asian Development Bank. Assessment of Power Sector Reforms in Viet Nam: Country Report. Asian Development Bank, Sept. 2015, www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/173769/vie-power-sector-reforms.pdf.

- CEICdata.com. Vietnam VN: Electric Power Transmission and Distribution Losses: % of Output. Ceicdata.com, Aug. 2018, www.ceicdata.com/en/vietnam/energy-production-and-consumption/vn-electric-power-transmission-and-distribution-losses–of-output.

- Einrac. Power Distribution Tariffs in India – 2024 a Comprehensive Analysis of Retail Supply Tariffs in India for FY 2024-25. Apr. 2024, eninrac.com/assets/upload/Power_Distribution_Tariffs_in_India_2024.pdf

- Jaganmohan, Madhumitha. India: Electricity Consumption 2021 | Statista. Statista, Jan. 2024, www.statista.com/statistics/383646/consumption-of-electricity-in-india/.

- Kala, Rishi. Govt Fixes RPO Target at 24.61 percent for FY23. The Hindu Businessline, 22 July 2022, www.thehindubusinessline.com/companies/govt-fixes-rpo-target-at-2461-per-cent-for-fy23/article65671834.ece.

- Maaz Mufti, Gussan, et al. Evaluating the Issues and Challenges in Context of the Energy Crisis of Pakistan. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, vol. 9, no. 36, Sept. 2016, https://doi.org/10.17485/ijst/2016/v9i36/102146.

- Ministry of Power. Guidelines Revamped Distribution Sector Scheme. 29 July 2021, powermin.gov.in/sites/default/files/uploads/Final_Revamped_Scheme_Guidelines.pdf.

- Năng lượng. Vietnam Energy: Current Status and Development Prospects. Năng Lượng Việt Nam Online, Jan. 2019, nangluongvietnam.vn/nang-luong-viet-nam-hien-trang-va-trien-vong-phat-trien-21878.html.

- NITI Aayog. Operational Performance. India Climate and Energy Dashboard, 2022, iced.niti.gov.in/energy/electricity/distribution/operational-performance.

- Press Information Bureau: Delhi. Government of India Launches Revamped Distribution Sector Scheme (RDSS) to Reduce the Aggregate Technical & Commercial (AT&C) Losses to Pan-India Levels. Pib.gov.in, 9 February 2023, pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1897764.

- Press Trust of India. India’s Emission Intensity Reduced by 33 percent between 2005 and 2019: Govt Report. The Hindu, 3 Dec. 2023, www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/energy-and-environment/indias-emission-intensity-reduced-by-33-per-cent-between-2005-and-2019-govt-report/article67600774.ece.

- Trading Economics. India GDP Grows Less than Expected in Q4. Tradingeconomics.com, Feb. 2023, tradingeconomics.com/india/gdp-growth-annual.

- Vietnam – Access to Electricity (% of Population) – 1990-2017 Data | 2020 Forecast. Tradingeconomics.com, tradingeconomics.com/vietnam/access-to-electricity-percent-of-population-wb-data.html.

- Vietnam GDP Annual Growth Rate. Tradingeconomics.com, 2023, tradingeconomics.com/vietnam/gdp-growth-annual.

- Vietnam Energy Online. Announced the Inspection Results of EVN’s Electricity Production and Business Costs. Vietnam Energy Online, Oct. 2024, vietnamenergy.vn/announced-the-inspection-results-of-evns-electricity-production-and-business-costs-33266.html.

- Lee AD, Gerner F. Learning from power sector reform experiences: The case of Vietnam. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 2020 Mar 2(9169).

- Do TM, Sharma D. Vietnam’s energy sector: A review of current energy policies and strategies. Energy Policy, 2011 Oct 1;39(10):5770-7.